Everyone knows all this has something to do with

the Kootenai Tribe's work to restore the

population of white sturgeon to the river. But

what exactly is going on? What is all the

dredging? What is the purpose behind all this

engineering of the river?

Everyone knows all this has something to do with

the Kootenai Tribe's work to restore the

population of white sturgeon to the river. But

what exactly is going on? What is all the

dredging? What is the purpose behind all this

engineering of the river?As far as what is going on with all the work being done just above the Kootenai Bridge, we have all the answers on that. But that part comes up a little later in the story.

First, you have to picture in your mind a time, not really that long ago, when giant sturgeon roamed the depths of the Kootenai River. Abundant in number, these fish provided a cultural subsistence fishery for generations of the Kootenai Tribe, and later a social and economic fishery for others who made their homes in the area we know today as Boundary County.

Similarly, burbot, a type of freshwater cod, was found in dense numbers in the river. They were once so abundant that burbot were often caught in large quantities. Catching burbot was often done in the wintertime, when one could cut a hole in the ice and put up a baited setline. Very often the burbot would be caught in the west side tributaries of the Kootenai, such as Smith Creek or Boundary Creek. Cutting a hole in the ice there would often reveal many burbot simply laying under the ice. The two to three foot long cod were often speared, and brought home loaded up in sleighs, or filled into gunnysacks.

Though the populations of these fish remained resilient in the face of heavy fishing for what might be

considered a remarkably long period of

time, eventually, in the later half of the

previous century, the toll that intense and

growing pressures of over harvesting began to

exact became more apparent as the numbers of

these fish dramatically fell.

considered a remarkably long period of

time, eventually, in the later half of the

previous century, the toll that intense and

growing pressures of over harvesting began to

exact became more apparent as the numbers of

these fish dramatically fell.But it was more than fishing that clobbered the Kootenai River's sturgeon and burbot. The river itself changed. Previously the Kootenai River had provided an environment in which the fish thrived. Gravel-laden river bottoms in areas where the sturgeon spawned provided a safe area for their eggs to fall, where they would stick to and be safely hidden amongst the rocks. Fish could hide or rest in deep pools scattered along the river, or in shaded spots along irregularly contoured riverbanks studded with logs or rocks. Vegetation grew along the banks that provided habitat and nourishment for land animals and insects that factored into the food chain for the fish. Floodplains, areas where the river overflowed its banks during high water seasons, provided important nutrients for the river system and habitat for some native fish, birds, and other animals.

Over the years, that version of the Kootenai River gradually changed. Dikes were built along the river banks to help control flooding. The dikes altered the natural vegetation along the river, and cut off the river's connection with its natural floodplains, many of which were converted to agricultural cultivation. In 1975, the newly-constructed Libby Dam was dedicated. The construction and operation of the dam altered the naturally occurring flows of the river, and had other effects including changes in temperature of the river water, and the way sediment was deposited along the river.

These changes dramatically improved the devastating effects of flooding along the river, helped to make farming the rich soil of the Kootenai Valley more practical, and together made a huge contribution to the economic viability, job creation, and progress of the residents of Boundary County.

But those changes to the Kootenai River altered the environment that helped many of the native fish of the river to flourish.

Gradually their numbers fell. The time came when you would crack open the ice at Smith Creek, and find no burbot there to gather into gunny sacks. The white sturgeon population of the Kootenai River shrank to the point that in 1994, they were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The burbot of the Kootenai River was proposed for Endangered Species Act listing in 2000, but were not listed as they did not meet the Act's "Distinct Population Segment" criteria. Still, as the burbot population dwindled, estimated at one point to number an estimated 50 fish, burbot were considered to be functionally extinct in the Kootenai River.

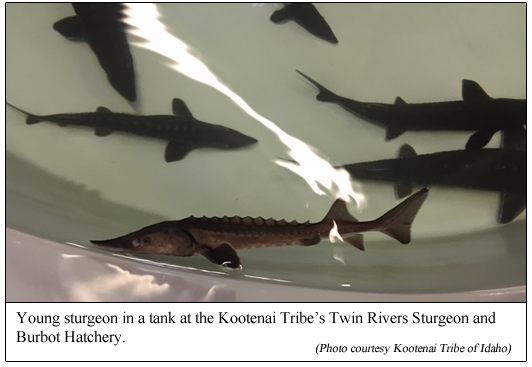

The Kootenai Tribe began their hatchery program in 1989, with efforts initially directed toward conservation of the Kootenai River's white sturgeon. In coordination with the University of Idaho the Tribe also began exploration of ways to raise burbot in a hatchery, something that had never been done before.

(Story continues below photo).

The efforts to grow and restock sturgeon and burbot back into the Kootenai River were remarkably successful, and over the years the tribe and its partners have released thousands of sturgeon and burbot into the Kootenai River system.

As the aquaculture program grew, it eventually became apparent the original facilities for the program, located near the Kootenai Tribal Reservation, were becoming too small for the growing and increasingly successful program.

A new hatchery was planned for the Twin Rivers area, at the confluence of the Moyie and the Kootenai Rivers. After two years of construction, the new, modern, state-of-the-art Twin Rivers Sturgeon and Burbot Hatchery was opened and dedicated last October.

Even though the program to raise and re-introduce the fish into the Kootenai River found great success, a significant issue still remained: The river itself. This was not the Kootenai River of 100 years ago, unencumbered by the Libby Dam, and unchecked by dikes along its banks—a river in which the sturgeon and burbot had once flourished.

"Although many factors have altered river habitat for sturgeon, burbot and other native fish," said Susan Ireland, Fish and Wildlife Department Director for the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho. "To our knowledge, construction and operation of Libby Dam and the elimination of the river's connection to its floodplain have had the most decisive and profound impacts."

"The construction of dikes to create farmable lands and to protect communities from flooding, cut the river off from and eliminated huge areas of historical floodplains," she explained. "The floodplains were really important because they provided nutrients that are essential to a healthy food web. The floodplains also provided habitats used by some native fish as well as other species such as birds. Floodplains provide the grocery store for the fish in the river.

"Construction of Libby Dam trapped sediments from the upper watershed behind the dam. Those sediments were also rich in important nutrients that fed the downstream river. In addition, the river would transport the sediments downstream during spring flows and deposit them on bars in the rivers, along the banks and on the floodplains, thus creating and maintaining habitat for native vegetation such as cottonwoods and willows that further contribute to the food web, create shadowy hiding places along the banks of the river, and stabilize the river banks.

"Historical and ongoing operations of Libby Dam, although important for flood control and power production, have significantly altered the way the river functions and the quantity and quality of fish and plant habitats. Spring flows have significantly decreased, altering the capacity of the river to transport sediment, gravel and rock. Winter flows have increased, and winter power peaking further exacerbates the situation by causing increased erosion of the riverbanks and scouring off young cottonwoods and other native plants that are trying to take hold.

Seasonal river temperatures are also altered by dam operations."

These newly-raised hatchery fish, carrying the hopes of jump-starting the resurgence of their populations in the Kootenai River, were being returned to a river with the same issues that had contributed to the decline of the original populations of sturgeon and burbot: loss of natural seasonal flows, altered seasonal water temperatures, changes in silt deposition, loss of natural flood plains, severe erosion of the riverbanks leading to loss of native riverbank vegetation and loss of irregularities--nooks and crannies--in the riverbank which provided pools, shaded areas, and eddies where fish could hide, rest, or feed.

It was apparent that for sturgeon and burbot to be sucessfully restored into the Kootenai, important river features necessary for thriving populations of these fish needed also to be restored.

It was also apparent that the Libby Dam and flood control measures, including the dikes, were necessary and important for the communities and people who lived along the river. Could there be a way to restore river features vital to the success of the sturgeon and burbot programs, and still work within the realities of the Kootenai River today, and the communities alongside the river?

“Finding a way to help the river work the way it is supposed to, without sacrificing flood control, and in a way that respects local land uses and community values, is what the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program is all about,” said Ron Abraham, of the Kootenai Tribal Council. “The Kootenai River is the backbone of our community, and we are all stewards of this unique piece of our cultural and natural heritage.”

"The challenge was to find ways to create those favorable habitat conditions while working within the existing constraints," according to Ms. Ireland. "This means, designing projects that will work and be sustainable within a range of different river flows. Making sure that the projects don’t increase flood risk to Bonners Ferry, or require additional flows that might increase flood risk."

"And since the majority of land along the Kootenai River is privately owned," added Mr. Abraham, "it also means working with willing private landowners to implement individual projects without doing harm to existing agricultural or other land uses."

In assessing how the problems would be addressed and programs designed and implemented, the Tribe established the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program, and engaged a multitude of stakeholders, put together multiple teams of knowledgeable scientists, and sought public input. Illustrating the breadth of involvement in the program, representatives from the following entities have partnered with the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho in participating in advisory teams or reviewing the habitat restoration program:

• Bonneville Power Administration

• Idaho Department of Fish and Game

• U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

• U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

• U.S. Geological Survey

• Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks

• Confederated Kootenai and Salish Tribes

• British Columbia Ministry of Forests Land Natural Resource Operations

• University of Idaho

• Bureau of Land Management

• Idaho Governor’s Office of Species Conservation

• Natural Resource Conservation Service

• Idaho Department of Environmental Quality

• Idaho Department of Lands

• Idaho Department of Water Resources

• Northwest Power and Conservation Council

• University of Lethbridge in Alberta

• University of California at Davis

• Bonners Ferry and Boundary County local governments

• Kootenai Valley Resource Initiative

In addition to these entities, private landowners and technical consultants including biologists, experts in groundwater and sediment transport, hydrology and engineering, geomorphology, river design, engineering, sediment transport and hydraulics, and modeling were also actively involved.

The charge was to develop a program that would best enhance the overall biologic system of the Kootenai River, identify and implement projects that would promote a thriving river ecosystem, and do so within the constraints of the river and community needs today.

"The Tribe’s overall approach to fish and wildlife and their habitats is fundamentally an ecosystem-based approach," said Ms. Ireland. By that we mean that the Tribe’s individual programs and projects at their core take into account the whole community of living creatures and the ways that they interact with other non-living components of the environment such as the water, air, soil.

"In terms of the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program, this means that we’re not just focusing on trying to restore one life-stage of one species of fish. Instead, we’re working to restore physical conditions that allow the river to act like a river, and allow the interconnected communities of plants and animals to fulfill their diverse roles. That is why the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program in combination with other projects, such as the nutrient restoration implemented by the Tribe and the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, is trying to restore conditions that will support a range of self-sustaining native fish, a healthy food web, and native plants. Since humans are also part of the ecosystem, all of this must also take into account the values and priorities of local and regional communities."

Investing time and significant resources into assessing what needed to be done and what could be done to restore some of the desirable physical conditions of the river, the Tribe and its cooperating partners identified several needs that could be addressed, and strategic locations along the river where interventions could best be employed.

Important river features that were needed, or other interventions that looked to be helpful as determined by the Tribe and its partners and consultants, included, for example:

Floodplain surfaces. "This is a key part of the Tribe’s restoration approach because floodplains support plant growth, and plants support the food web, which in turn supports all life in the river," said Tom Parker, a plant ecologist who is part of the program's design team.

"When Libby Dam began operations," he continued, "Kootenai River flows were reduced so much that the river no longer flooded its historical floodplain often enough to sustain many of the native riparian plants [plants occurring naturally along the riverbank]."

The plan is to create new floodplain surfaces along the course of the river, and establishing these surfaces at an elevation that will be watered only part of the year.

"By establishing new floodplains at a lower elevation, we will be able to allow native vegetation to develop at an elevation that can be sustained by the river’s current dam operated flows. This will also help restore some of the vital floodplain functions that were lost when the river was disconnected from the floodplain by dikes," Mr. Parker said.

"Removal of current river dikes is not planned in any of the Tribe's projects," added Ms. Ireland. "All projects are also planned so that they will not increase flood risk to the community."

Deep pools. These pools have been found to provide habitat where sturgeon can "stage" (which is to get ready) for spawning, and a place for these and other fish species to feed and rest.

Sizing the river channel. The old river channel was created by river flows that were much higher than those seen today with operation of the Libby Dam. To help adjust the river channel to today's dam-managed flows, the program is trying to construct a more pronounced river channel, by excavating pools and adding structures or islands that constrict flows.

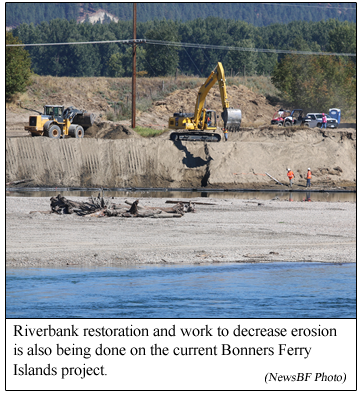

Address erosion of the riverbank, and enhance "riverbank complexity." The lack of opportunities for the river to “let off steam” at higher flows by flowing into the historical floodplain, along with winter power

operations

that raise and lower the river elevation

quickly, have helped create steep banks with

severe erosion in some areas. The lack of plants

and tree roots that help stabilize the river

banks have made them more prone to erosion. In

places where erosion is particularly severe,

with resulting sediment falling into the river

and threatening spawning areas, banks are

regraded to more sustainable angles. These

regraded banks are stabilized in the short run

with logs and brush that are partially buried

into the banks to slow the water, allowing

newly-planted vegetation to take root and become

established. In the long run, the newly

planted-vegetation should stabilize the

riverbanks as it matures, slow the water near

the banks and prevent erosion, and in general

provide more "complex" banks and better habitat

for fish and other animals.

operations

that raise and lower the river elevation

quickly, have helped create steep banks with

severe erosion in some areas. The lack of plants

and tree roots that help stabilize the river

banks have made them more prone to erosion. In

places where erosion is particularly severe,

with resulting sediment falling into the river

and threatening spawning areas, banks are

regraded to more sustainable angles. These

regraded banks are stabilized in the short run

with logs and brush that are partially buried

into the banks to slow the water, allowing

newly-planted vegetation to take root and become

established. In the long run, the newly

planted-vegetation should stabilize the

riverbanks as it matures, slow the water near

the banks and prevent erosion, and in general

provide more "complex" banks and better habitat

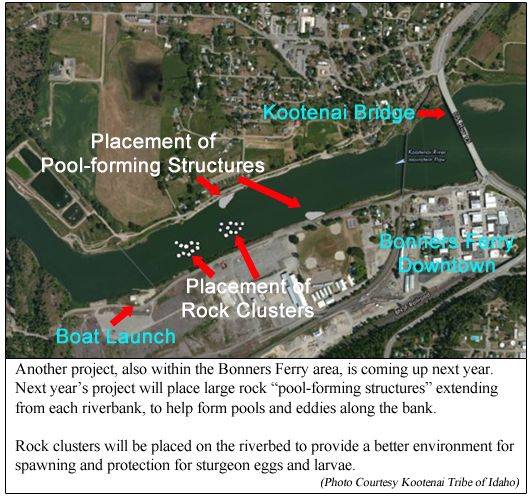

for fish and other animals.Plans were also made to provide structures extending from the bank into the river ("pool-forming structures") with the intention of further protecting the riverbanks, creating eddies that many fish use, and to help direct river flow. It was hoped that these structures would slow down water along the bank to help create more complex aquatic habitat.

Placement of instream structures. This includes placing rock or gravel onto the riverbed, or placing structures directly into the river to help form pools within the river or to create other desirable hydraulic effects.

Side channels. Reconnecting long-blocked natural river side channels, or constructing new side channels where needed, in hopes of providing habitat for fish, reducing sediment in the river overall, and help reconnect floodplains to the river where possible.

These are a few examples; other methods, techniques, and river interventions are also available to enhance the river's ecosystem.

The over-arching idea of all this, according to Ms. Ireland, "is to restore more natural in-river conditions to help the river heal itself within the constraints of Libby Dam operations for power and flood control, and while respecting existing land uses.”

Along with identifying processes to enhance the river environment for fish and other species, the planners identified also specific parts of the river where interventions seemed to be most needed.

Once all the plans were set, goals identified, and logistics worked out, actual work on the overall program began in the summer of 2011.

From 2011 through 2014 there were seven projects completed under the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program. This included two projects in 2011, two in 2012, two in 2013 and one in 2014. The six projects completed from 2011 through 2013 were all in the portion of the river known as the Braided Reach, the area immediately around Bonners Ferry and extending upstream as far as the Twin Rivers area where the Moyie River joins the Kootenai.

Those projects involved restoration of eroded riverbanks and measures to prevent significant future erosion, restoration of floodplains, restoration of side channel habitat, excavation of pools, construction of pool-forming structures, and planting of riverbank vegetation

The 2014 project took place in the area of the river known as the "Meander Reaches," which is the slow, winding, meandering length of the river that extends downstream from Bonners Ferry to the Canadian border. In this project, rocky material was placed on the riverbed in locations near Shorty's Island and near Myrtle Creek—areas where sturgeon are known to spawn, but seem to have diminished survival rates due to less-than-optimal sand and clay river bottoms. In ideal conditions, it appears that sturgeon eggs released by female fish, being very sticky, adhere to rock or gravel on the river bottom, where the eggs and the hatched larvae can hide and be protected. It is hoped that adding rock and gravel to these areas where sturgeon are known to spawn will improve chances for survival of these young fish.

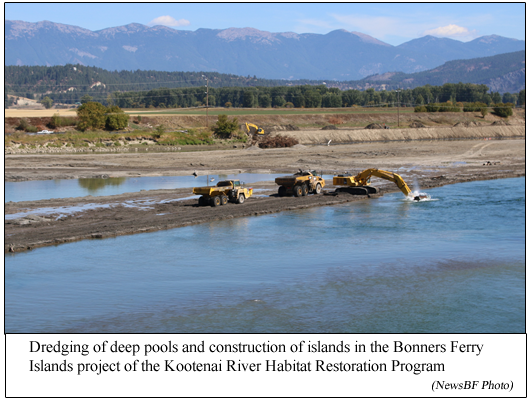

And that brings us to 2015, and what is going on right now in the Kootenai River just upstream from the Kootenai Bridge in downtown Bonners Ferry. That work is known as the Bonners Ferry Islands project.

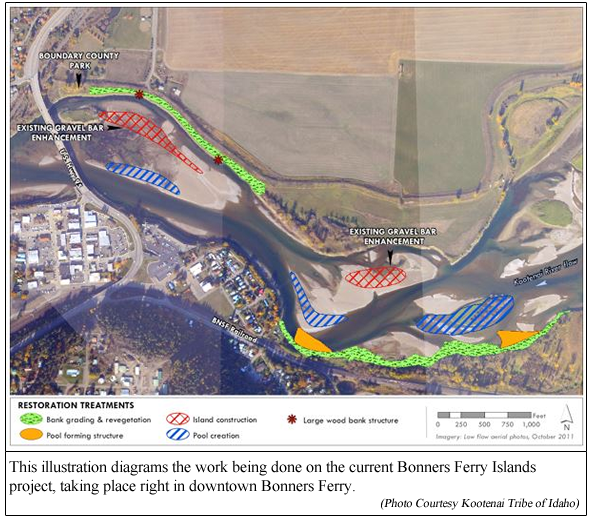

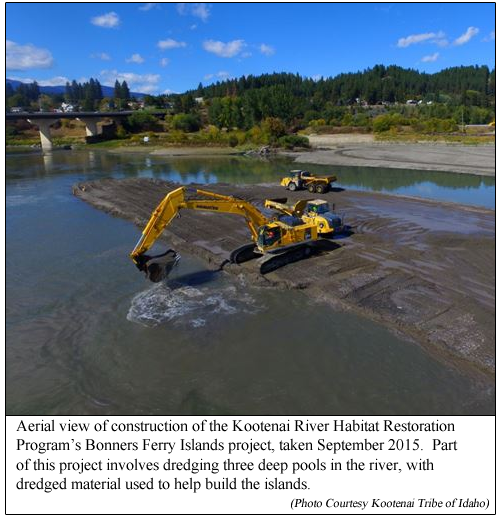

The Bonners Ferry Islands project, which we get to witness every day, involves excavation of three deep pools in the river, which is what we see the large excavators working on in the river. These deep pools will provide habitat for spawning staging for Kootenai sturgeon, along with deep areas where burbot and other native fish can feed and rest.

These deep pools are part of a chain of pools being created throughout the Braided Reach area of the river.

(Story continues below photo).

Material dredged from the excavated pools is being used to construct the Bonners Ferry Islands, which will provide floodplain surfaces and will be partially vegetated, providing floodplain habitat that should contribute important nutrients to the food web in that part of the river.

These islands also affect size of the river channel in that area, creating a more pronounced channel to better match the lower scale of flows seen under Libby Dam operations, and hopefully improving the ability of the river to transport sediment.

(Story continues below photo).

The Bonners Ferry Islands project also involves construction of four structures that will extend out from the riverbank into the river channel to help protect the riverbanks and help form areas of eddies. This project also includes work to grade and improve eroded river banks and revegetate the area.

Construction of the Bonners Ferry Islands project will continue into November, then will be put on hold until July of next year. It is anticipated that the overall Bonners Ferry Islands project will be completed by November of next year.

This project is being done just upstream from areas where sturgeon are known to spawn.

And that is what is going on with all the heavy equipment we see today in the river, and all the dredging going on, and why all that work is being done.

The Kootenai Tribe plans are to begin construction of another project next year, just downstream of the Kootenai Bridge. In that upcoming project, two rock spurs will be added along the riverbanks to create more complex riverbank in-water habitat, and clusters of rocky material will be placed on the riverbed in efforts to enhance survival of larval and other young sturgeon. That work will also be seen from Bonners Ferry, this time downstream from the Kootenai Bridge.

(Story continues below photo).

Additional projects downstream and upstream from Bonners Ferry are currently in the concept and planning stages. Construction of those projects is tentatively planned to begin in 2017 and 2018.

A few questions naturally arise in considering this comprehensive plan to restore habitat in the Kootenai River. Likely the first question of all is,

1. How is this all being paid for?

Under the Northwest Power Act passed by Congress in 1984, the Bonneville Power Administration is required to mitigate losses to fish and wildlife affected by the federal hydropower system in the Columbia River Basin (of which the Kootenai River is a part). Around $250 million is made available each year for this program. That $250 million comes from fees built into regional power rates. “This money is distributed throughout the entire Columbia River Basin through a competitive process managed by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, which incorporates rigorous science and policy reviews of all proposals,” observed Ms. Ireland.

The Kootenai Tribe competed for and won funding for the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program through this process. “We’re really excited about the opportunity to bring these resources back to the Bonners Ferry community,” said Ms. Ireland. “It’s a question of fairness. Libby Dam plays a really important role helping to protect the Bonners Ferry area from flood risk. However, as part of the federal Columbia River power system, a lot of the power and revenue benefits of the dam flow downstream to other communities. Additionally, the vast majority of the mitigation funding is spent downstream,” she said.

“Being able to bring some of those resources back home to invest them on the ground in Bonners Ferry is really important. We are glad that it can provide economic benefit to the community as well as benefit to the fish.” Ms. Ireland concluded.

Hence, the primary funding for the Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program is from this mitigation funding of the Bonneville Power Administration through the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program.

In 2011, the Kootenai Tribe was awarded a grant of $250,000 from the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. In 2013, BNSF Railway contributed $160,000 to support the Middle Meander project. To date, those grants and the BPA mitigation money are the only direct sources of funding for the program.

What has it cost? From 2011 through 2015, the costs of individual Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program projects have varied based on the amount and type of work required. Averaging about two projects per year since 2011, construction costs for the overall program have ranged from approximately $1.7 million to $4.5 million per year.

A separate program administered through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Services made funding available to private landholders along the river to implement approved treatments on their private lands that complemented the overall Restoration Program. This program was in effect from August 1, 2011 through September 30, 2015. At least 15 landowners participated in this program and had projects done on their lands through contracts administered and managed between 2011 and 2015. Participation in this separate funding program was at the discretion of the landowner.

(Story continues below photo).

2. Once all these projects are completed, the Libby Dam and the dikes will still be there. Won't river flows and erosion eventually degrade all this work, eventually returning the river to a condition similar to how it was when the program was started?

Ms. Ireland answers this question: "The Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program projects are designed to be self-sustaining given current conditions. While it may be necessary to do some minor maintenance on the projects as they are first getting established (for example fence repair and planting) the projects are designed to work with the range of the river flows.

"In thinking about the long-term performance of the program," she continued, "it is important to understand that rivers are by their very nature dynamic and constantly adjusting and changing. That’s true even of regulated rivers like the Kootenai. That’s a good thing from an ecosystem perspective. The Kootenai River Habitat Restoration Program projects are not designed to create permanent non-changing structures or features. We would say that the projects are designed to be dynamically stable. They are designed to help restore and jump-start the natural processes in the river in a way that cannot be accomplished through dam operations alone."

"An important objective of the work being done in the Braided Reach in particular,” explained Matt Daniels, a river design engineer working for the Tribe on the program, “is sizing the river channel to better match the current dam modulated flows and the sediments loads that the river is able to transport under those flows. Sizing the river channel to better match these current conditions will also help to make the conditions we’re trying to create in the river more sustainable."

3. Are we seeing any positive results from all the work that has been done so far in already-completed projects in the program?

"Yes," said Ms. Ireland. "From a physical standpoint the projects are performing as modeled, they are changing the river hydraulics the way we hoped they would, they are creating the alcoves and eddies we wanted to see, the pools built so far are sustaining themselves with one even getting deeper.

"As for the fish response, we have observed kokanee spawning in the newly restored side channels and trout occupying the new alcoves and eddies. Idaho Department of Fish and Game has monitored burbot and sturgeon spawning over the new substrate [material on the river bottom]. There has been an overall increase in the size and number of trout in the reaches upstream of Bonners Ferry and we have heard very positive reports of improved trout fishing as a result of the nutrient restoration program and the habitat improvements.

(Story continues below photo).

4. Are people permitted to boat around or past the work going on right now next to the Kootenai Bridge?

Yes, people are permitted to boat around or past the work. However, officials advise that boaters should be cautious in the river construction area.

5. And maybe one of the bigger questions in the back of many people's minds—

Is it anticipated that one day there will again be public fishing for sturgeon and burbot in the Kootenai River?

"The goal of this project," said Ms. Ireland, "in combination with the conservation aquaculture program and nutrient program, is ultimately to restore self-sustaining and harvestable populations of sturgeon, burbot and other native fish."

The end result of this program is to one day have a Kootenai River with a healthy ecosystem, supporting a variety of fish, wildlife, and vegetation, and meeting the needs of the communities and people who make their homes along the Kootenai River region. And that includes having healthy, thriving populations of Kootenai river white sturgeon, burbot, and other varieties of fish.

“By helping the river to provide the habitat that our native fish need, we’re investing in the river, the fish, and in our local economy,” said Gary Aitken Jr., Tribal Chair of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho.