Local hero being considered for Medal of Honor

By Mike Weland

|

| Navy-Marine Corps Medal of Honor |

They were one of seven teams from the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division, sent out in what was dubbed Operation Kansas, an extensive reconnaissance effort designed to find the headquarters of the 2nd North Vietnamese Army near the Que Son Valley.

For the next few days, the Marines of Recon Team 2, on what became known as Hill 488, dug in and reported enemy movement and called in successful artillery strikes on targets of opportunity in an uneventful mission.

On the morning of June 15, SSGT Howard, despite concerns that the enemy, who by the accurate artillery fire falling on them might know they were under observation, and from where, radioed back to his battalion commander asking permission to stay one more night.

Permission was granted.

|

| Nui Vi, called Hill 488 by U.S. personnel , was the site of a battle so fierce those who've studied it call it a modern-day Alamo ... except that thanks to the heroism of one man, American Marines lived to tell the story. |

On the night of June 15, a nearby Army Special Forces team leading a Civilian Irregular Defense Group patrol radioed a warning that they’d spotted a battalion of up to 250 Vietnamese regulars closing in on Hill 488.

Too late to evacuate, the men manning the observation post did what they could to improve their defenses and hunkered down.

At about

It wasn’t a battalion, as anticipated, but a regiment, though the 18 men on the hill didn’t know it at the time. All they knew was that they were surrounded by an aggressive, determined and well-led force that seemed to have no end.

|

| Marine Lance Corporal Ric Binns (foreground) and team members Tom Powles, Joseph Kosoglow and William Norman. |

For the next seven hours, during which six members of the besieged platoon were killed and everyone else wounded in the opening salvos of the battle, Lance Corporal Ricardo Binns, now of Bonners Ferry, rallied the survivors, directing fire, passing around ammunition, tending to the wounded, as enemy soldiers surrounding their position poured down a continuous rain of grenades and withering fire from heavy machine guns, 60mm mortars, AK-47 and small arms.

Overhead, close air support aircraft circled helplessly, providing fire where they could, but unable to do so effectively as the enemy was too close to the embattled but tenacious Marines. With flares parachuting down from the circling planes, those few recon Marines repelled several coordinated attacks and relentless and continuous harassing fire.

|

| An artist's rendition of the Battle of Hill 488, as described by Ric Binns, that appeared in the May, 1968, issue of Readers Digest. |

A pair of helicopters

attempted to land on the hill at around

|

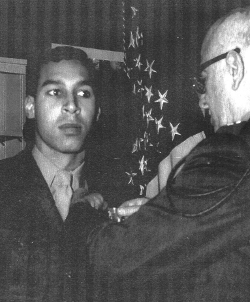

| Lance Corporal Ric Binns being awarded the Navy Cross, the service's second highest award for valor in combat. |

In the final tally, the 18 men on the hill through that endless night killed an estimated 200 enemy to the six men they lost, with Binns credited with at least 30 kills.

In the aftermath of the battle, Howard was promoted to Gunnery Sergeant and presented the Medal of Honor. He died in 1993 at the age of 64.

Binns, shuffled off to a series of hospitals and kept in near solitary confinement, was one of four members of the recon platoon to be awarded the Navy Cross, that service’s second highest award for valor, two of those posthumously. Thirteen Silver Stars were awarded the rest of the team, four of them posthumously. Every member of the team was awarded the Purple Heart, Binns his second.

|

| Ric Binns shaking hands with President Lyndon B. Johnson during the ceremony at which the Medal of Honor was conferred on Staff Sergeant Jimmie Howard August 21, 1967. |

In the early 1970s, a young

Marine Corps officer, Robert Adelhelm, studied

the Battle of Hill 488 at Marine Officer’s

|

| Marine Lieutenant Colonel Robert Adelhelm, retired, who studied the Battle of Hill 488 while in officer's school, and who came to believe that a fellow Marine had been denied due honor for valor above and beyond the call of duty. |

What began as a matter of interest grew to become a mission for the retired Recon Marine, who is convinced by the record and by what he’s learned that the Marine Corps, for whatever reason, deprived a true hero of the recognition he deserved, the Medal of Honor. Worse, he said, was the way the Marine Corps treated a hero after shunting him out of the service.

“They gave this man a

general discharge,” Adelhelm said. “A Marine who

volunteered for

Binns’ less than ideal conduct as a garrison Marine, he said, was partially to blame.

“The Marine Corps rates every Marine on conduct, and takes away points for bad marks on your service record,” he said. “To get an honorable discharge, you have to have a minimum of four points. Ric had 3.75. In light of the Navy Cross, that shouldn’t have mattered. But that medal wasn’t even listed on his DD-214.”

Because of the less than honorable discharge, Binns found it hard, once he was out of the hospital, to find a job. When he went to VA Hospitals for needed treatment, he was shuttled to the back of the line.

“Back then, your military service meant something, and a less than honorable discharge slammed a lot of doors shut in your face,” Adelhelm said. “It took him 10 years of fighting a bureaucracy to have his record corrected and his discharge status upgraded to ‘Honorable.’ For 10 years, Ric Binns was denied even the recognition and privilege that comes with an honorable discharge and with wearing the Navy Cross.”

A more subtle reason for what Binns endured, he said, may have been the times, a period of national unrest as protest against the Vietnam War set cities across the country aflame, the color of Ric Binns’ skin and the fact that Binns refused to die.

“You have to remember the times,” he said. “In 1966, it was a racially charged environment. I think it’s safe to say there were some who didn’t want to put a Medal of Honor on a face that wasn’t white.”

Just reading the citations of the medals awarded, he said, makes it clear that an injustice was done.

“I read all the citations arising from the battle and there were none that compared to Binns.’” he said. “If you read Binns’ Navy Cross citation, it reads like a Medal of Honor citation.”

More telling yet, he said, are the very words of Jimmie Howard in his statement on the battle, written shortly after he’d come down from Hill 488:

“On

“It’s clear from that statement,” Adelhelm said, “that Howard believed Binns merited the Medal of Honor.”

Another factor in his belief that the honors for the actions of the brave Recon Marines and Navy Corpsmen on that hill that night were misappropriated is the speed at which those medals were conferred.

“Award package,” he wrote

in his recommendation, “was submitted to

Division on June 20th, 4 days after

the battle, and division forwarded the package

to FMF (Fleet Marine Force) Pacific on June 22nd

… LCpl Binns was evacuated after the battle to

Chu Lai hospital on June 16 and was unable to

walk … LCpl Binns was informed on June 16th,

within hours of his evacuation from the battle,

he was going to be awarded the Navy Cross by his

battalion commander … LCpl Binns was transferred

to the DaNang Hospital after being operated on

at Chu Lai Hospital, was eventually transferred

to the Naval Hospital Guam on June 27, 1966, St.

Albans Hospital, NY on August 10, 1966 and

administratively transferred to MB (Marine

Barracks) Brooklyn Navy Yard until his discharge

in November, 1966 … LCpl Binns was not visited

or contacted by any members of his battalion

while in DaNang or the stateside hospital … LCpl

Binns was not debriefed on the patrol nor did he

provide any information regarding the subsequent

award recommendations … There is no evidence to

substantiate witnesses being interviewed at the

battalion or division level prior to the awards

package being forwarded to

You can read Adelhelm's full report and find other documentation regarding his recommendation on his website, https://sites.google.com/site/jaxsemperfidelissociety/stolen.

The Marine Corps hierarchy of the time, he fears, had pre-determined which men on that hill would get what awards even before the battle had ended, and the highest ranking member would get the highest honor.

“In the past,” Adelhelm wrote, “history has shown that heroic behavior in battle seems more widespread than awards of the Medal of Honor, and this case is no exception. There have been cases where an ‘unacceptable’ individual who exhibited extraordinary bravery may not be recommended and a more ‘acceptable’ individual chosen that has the ‘hero personna’ versus the actual individual who performed the heroic acts. This, coupled with the unrealistic ‘one-man-per-battle’ limit on the MOH that exists, ensures that some will not get their rightful recognition despite any heroic actions and the impact they had and the outcome of the situation. In this case, perhaps some at the battalion and division levels decided a Marine need to not only be very brave in a given action, but also be politically acceptable.”

While hard to define or classify, Ricardo C. Binns isn’t white.

|

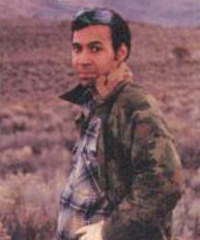

| Ric Binns, circa 1990. Now living in Bonners Ferry, he's changed but little over the ensuing years. |

Jimmie Howard was the

epitome of a Marine non-commissioned officer,

tall, straight, a former Marine Corps Drill

Instructor and recipient of the Silver Star and

two Purple Hearts in

Adelhelm doesn’t begrudge Jimmie Howard the Medal of Honor, nor does he insinuate that this decorated Recon Marine didn’t deserve it … the Medal of Honor, he said, is a medal conferred by a grateful nation, not sought by those upon whom the award falls.

The people in charge at the time, all the way up to President Lyndon B. Johnson, who linked the clasp of that pale blue ribbon on only the sixth U.S. Marine to be so honored for service during the Vietnam War on August 2, 1967, agreed that Jimmie Howard was deserving of this nation’s highest honor for his actions in that battle.

Adelhelm believes that Jimmie Howard and Lance Corporal Ric Binns were both victims of a bureaucracy more interested in preserving an image rather than in bestowing honors for valor where due.

A bit of history gives grounds for his concerns.

Since the inception of the Medal of Honor during the Civil War, 3,464 have been conferred, a disproportionate number of them during that war because the high standards associated with the Medal of Honor only came later. Of that number, 88 have been bestowed on men of color.

Robert Augustus Sweeney, a Canadian who emigrated to the U.S. and enlisted in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, is the only black man to have been awarded the Medal of Honor twice, both times for saving the lives of shipmates. His is a distinction shared by a total of 19 heroes, all but one white, to be so honored twice.

In all, 25 men of color awarded the Medal of Honor were so recognized for their actions in the Civil War. The only Medal of Honor conferred by this nation to a woman also came during the Civil War when President Andrew Johnson presented it to Dr. Mary Walker. While she wore her Medal proudly until she died in 1919, Congress had rescinded her award in 1917, along with some 900 others. It wasn't until 58 years later, on June 10, 1977, that her valor was reaffirmed when President Jimmy Carter, with the approval of Congress, restored her Medal of Honor.

During the Indian Wars that

followed on the heels of the Civil War, 18

“Buffalo Soldiers” were presented the Medal of

Honor. Citations were brief, "Gallantry in the

fight between Paymaster Wham's escort and

robbers. Mays walked and crawled 2 miles to a

ranch for help," read that presented to Isaiah

Mays, a black Army corporal serving with the 24th

Infantry Regiment in

Six men of color were presented the Medal of Honor during the Spanish American War, five “Buffalo Soldiers,” four of them for action in a single engagement, and one U.S. Navy sailor, honored for "performing his duty at the risk of serious scalding at the time of the blowing out of the manhole gasket on board the vessel, Penn hauled the fire while standing on a board thrown across a coal bucket 1 foot above the boiling water which was still blowing from the boiler."

|

| The grave of Army Corporal Freddie Stowers at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, France. It took 73 years for this nation to recognize his valor. |

After his death, Corporal Stowers was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but the recommendation was never processed. Three other black soldiers were also recommended for Medals of Honor in that war, but were instead awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

In 1990, at the instigation

of Congress, the Department of the Army

conducted a review and the Stowers

recommendation was uncovered. Subsequently, a

team was dispatched to

During World War II, no Medals of Honor were bestowed on black men, though black men comprised nearly a quarter of the forces this nation sent to fight.

|

| Vernon Baker, St. Maries, Idaho, shaking the hand of President Bill Clinton after receiving the Medal of Honor, 53 years after his brave actions on a battlefield in Italy during World War II. |

The other six were awarded posthumously.

Two black Army soldiers, both members of the 24th Infantry Division, won the Medal of Honor during the Korean War, both posthumously.

In Vietnam, 20 American servicemen of color were awarded the Medal of Honor, including five black Marines, all of them posthumous, and all awarded for their actions in saving the lives of fellow Marines by fearlessly giving up their own, most often by diving on a grenade.

And all for actions that took place well after June 15, 1966, when a young U.S. Marine of color from the mean streets of the Bronx held a team of 18 men together through the worst kind of hell against an enemy force estimated in the hundreds and lived, and who, in the process, kept a number of the men he served with alive to come back and tell the tale.

“Ric Binns, on that night, epitomized everything this nation defines as heroic,” Adelhelm said. “That he’s been treated the way he has is a smear on both the United States Marine Corps and this nation. At the least, the Marine Corps owes this man an apology. At best, the Corps can do what’s right and give this man the credit he’s due.”

Well familiar with military bureaucracy, Adelhelm began wading through the mountains of red tape to correct what he sees as a stain on his beloved Marine Corps, and, by default on his nation.

In May, 2010, he submitted a 10-page recommendation that Binns’ Navy Cross be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

He did much more than his homework. Over the course of years, he compiled interviews with the surviving members of the recon unit, verified what he was hearing by interviewing others who were on the ground and in the air as headquarters scrambled to salvage what appeared, at the time, to be a lost cause. He gained access to 57 taped interviews of the surviving platoon members and tried his best to talk to the officers who processed the paperwork after those 18 men won that battle.

The men on the ground and in the air, he said, all told the same story … L/Cpl Ricardo C. Binns was the factor, the one Marine on that hill who used what little he had at his disposal to disorient, confuse and ultimately defeat a tenacious enemy intent on using superior numbers and overwhelming firepower to defeat an exposed and lightly armed enemy. Long after being given up for lost, Ricardo Binns, by personal example, imbued in the men the willingness to keep on fighting, even though he didn’t technically hold the rank to lead.

At first, Adelhelm ran into

a wall of apathy. Because more than two years

had passed, the recommendation had to have a nod

to proceed from a sitting U.S. Congressman

representing the proposed recipient’s current

home state, in this case,

He submitted the recommendation to Jim Rische and heard nothing.

Then Raul Labrador came to office, and the new Congressman gave it his signature.

The recommendation, Adelhelm said, is now where it should have been in the weeks after the Battle of Hill 488, going through Marine Corps channels.

With

“The Marine Corps now has the package and will make a decision sometime in June,” he said.

But even if they give it their stamp of approval, Adelhelm said, the request still has a long way to go, and local support can help.

Those interested in supporting this effort can best do so, he said, by encouraging the Idaho Congressional delegation to see this recommendation through.

Senator Mike Crapo can be reached by writing him at 239 Dirksen Senate Building, Washington, DC, 20510, or by calling (202) 224-6142; Senator Jim Risch, 438 Russell Senate Building, Washington, DC, 20510, (202) 224-2752, and Congressman Raul Labrador, 1523 Longworth House Building, Washington, DC, 20510, (202) 225-6611.

If the United States Marine Corps does right by this hero and recommends approval, the application gets bumped up through myriad channels all the way to Commander in Chief.

If the President of the United States approves, a ceremony will be set and the Medal of Honor conferred.

If that happens, Adelhelm says, a great wrong will be made right.

And Ricardo C. Binns will again be entitled to do something he's been denied since his less than honorable discharge in 1971, don a uniform he still cherishes ... that of a United States Marine.